Building Production-Ready AI Agents

Everyone's building AI agents in 2025. Few are shipping them to production. The issue isn't intelligence — it's architecture. This article breaks down some challenges of production-ready agents and how Lampi AI handle complex workflows reliably with AI agents.

Here's what nobody's saying out loud about AI agents in 2025: most of these are held together with duct tape and prayers.

They work in demos. They work on the happy path. But put them in real production environments? They fall apart. They hallucinate. They loop forever. They confidently do the wrong thing.

And in industries with strict professional requirements— in particular finance or legal — where higher standards are imposed on quality, accuracy, depth, and logical coherence, you can't afford an agent that crashes at 2am.

We know because we've been there. We've spent thousands of hours building Lampi AI— a multi-agent architecture that actually works. Reliably. At scale.

This article explores the real challenges that emerge when building production-ready AI agents (2) and how we handle even the most complex tasks with our AI agents: from drafting fact-based investment memos, pitch decks, or reviewing hundreds of agreements in a single agentic flow (3).

But before we dive into the hard problems, let's establish a shared vocabulary (1). Because "AI agent" might be the most overloaded term in tech right now.

1. What Is an AI Agent, Really?

The word "agent" gets thrown around so loosely it's nearly lost all meaning. A chatbot with API access? Agent. A workflow that crashes after three steps? Agent. A simple prompt chain with a polished UI? Also agent, apparently.

Definition

While there is no strict definition of an AI agent, it can be described as a system where an LLM dynamically decides what actions to take to accomplish a goal. Agents have been described as AI systems capable of autonomous reasoning and goal-driven action in dynamic environments (Nisa et al. 2025) integrating perception, planning, and execution to operate continuously on open-ended tasks.

AI agents can handle variation. They can reason through ambiguity. They can adapt when things don't go as expected.

But — and this is the catch — LLMs are probabilistic. They don't follow rules; they follow patterns. They can hallucinate with complete confidence. They can get stuck in loops. They can misunderstand your instructions in ways that seem impossible.

Managing this uncertainty is where 90% of AI agent projects fail.

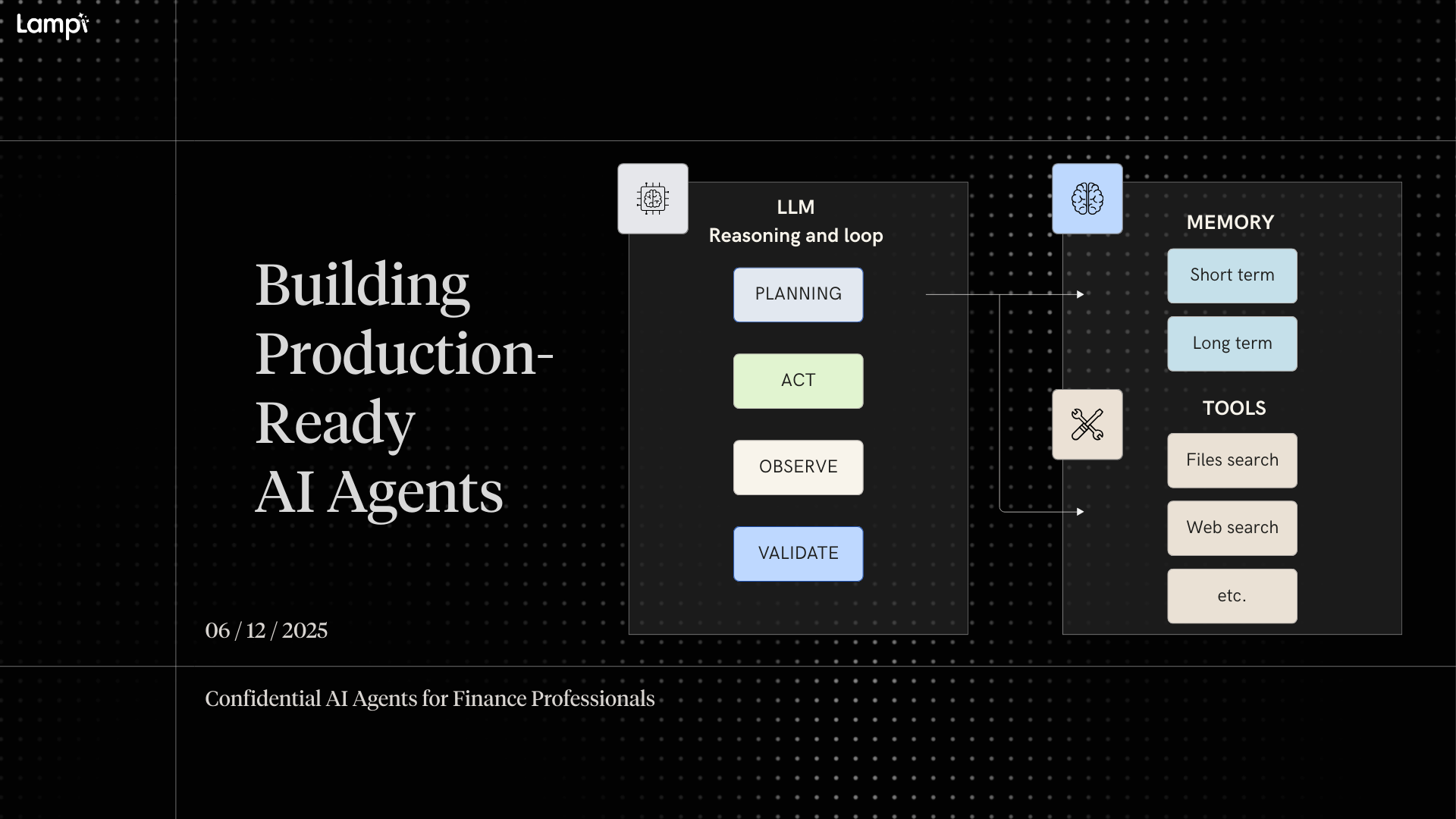

The Building Blocks of Every AI Agent

Every AI agent—simple or complex—is built from the following components.

1. Reasoning Engine (LLM)

The LLM. It acts as the brain, orchestrating decisions and planning. It interprets what you want, plans how to get there, and decides what to do at each step. The reasoning layer includes:

- Goal interpretation: Understanding intent

- Planning: Breaking complex tasks into actionable steps

- Decision-making: Choosing tools, parameters, next moves

- Coherence: Staying on track across multiple iterations

2. Memory (The Context)

Memory enables capturing and storing context and feedback across multiple interactions. Memory is how agents know what's happening. It operates at two levels:

- Short-term memory is the immediate context—the current conversation, recent tool outputs, the active plan. This lives in the LLM's context window.

- Long-term memory persists beyond any single session through retrieval. User preferences. Patterns learned over time, etc.

Managing what goes into memory is complex. Context windows are finite, even with 1M tokens window, a lot of questions arise: what automatically stays in the agent's memory? What gets compressed? What gets retrieved? How to decide what's obsolete? This is where most implementations struggle.

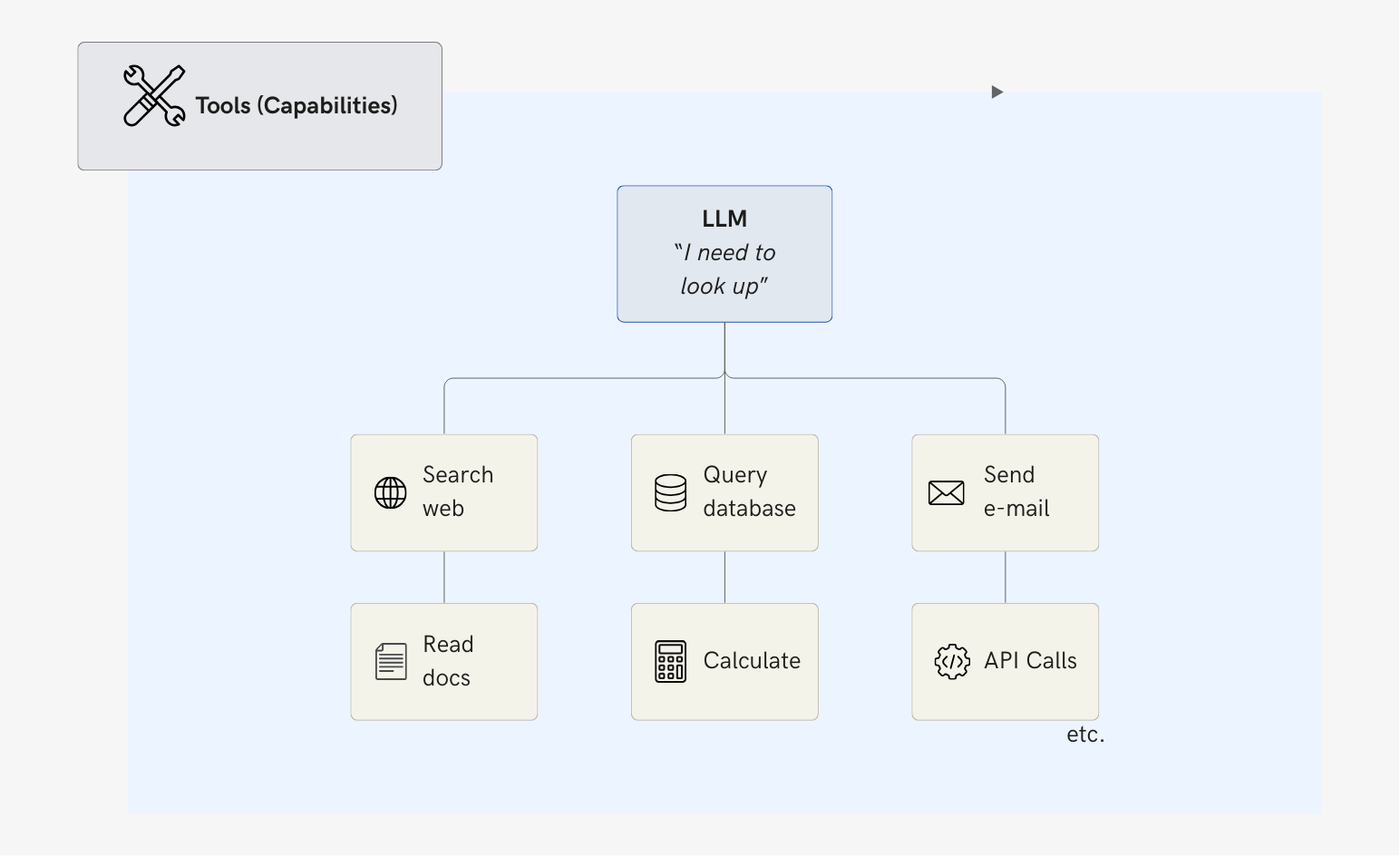

3. Tools (The Capabilities)

An LLM alone is trapped in a bubble. It can't search the web. It can't query databases. It can't read documents, send emails, or call APIs.

Tools expand the capabilities of AI agents beyond the knowledge of their original dataset and allow them to dynamically interact with external resources and applications, real-time data, or other resources. These tools are used to perform specific tasks, like searching the web, retrieving data from an external database, or reading or sending emails that help the agent achieve their target.

A tool can be a simple function such as a calculator, or an API call to a third-party service such as stock price lookup.

When an agent decides "I need to look up this company's revenue," a tool executes that search and returns the results.

BUT: more tools = more problems. Every tool added is another choice the LLM can get wrong. Another parameter it can hallucinate. Another failure mode to handle.

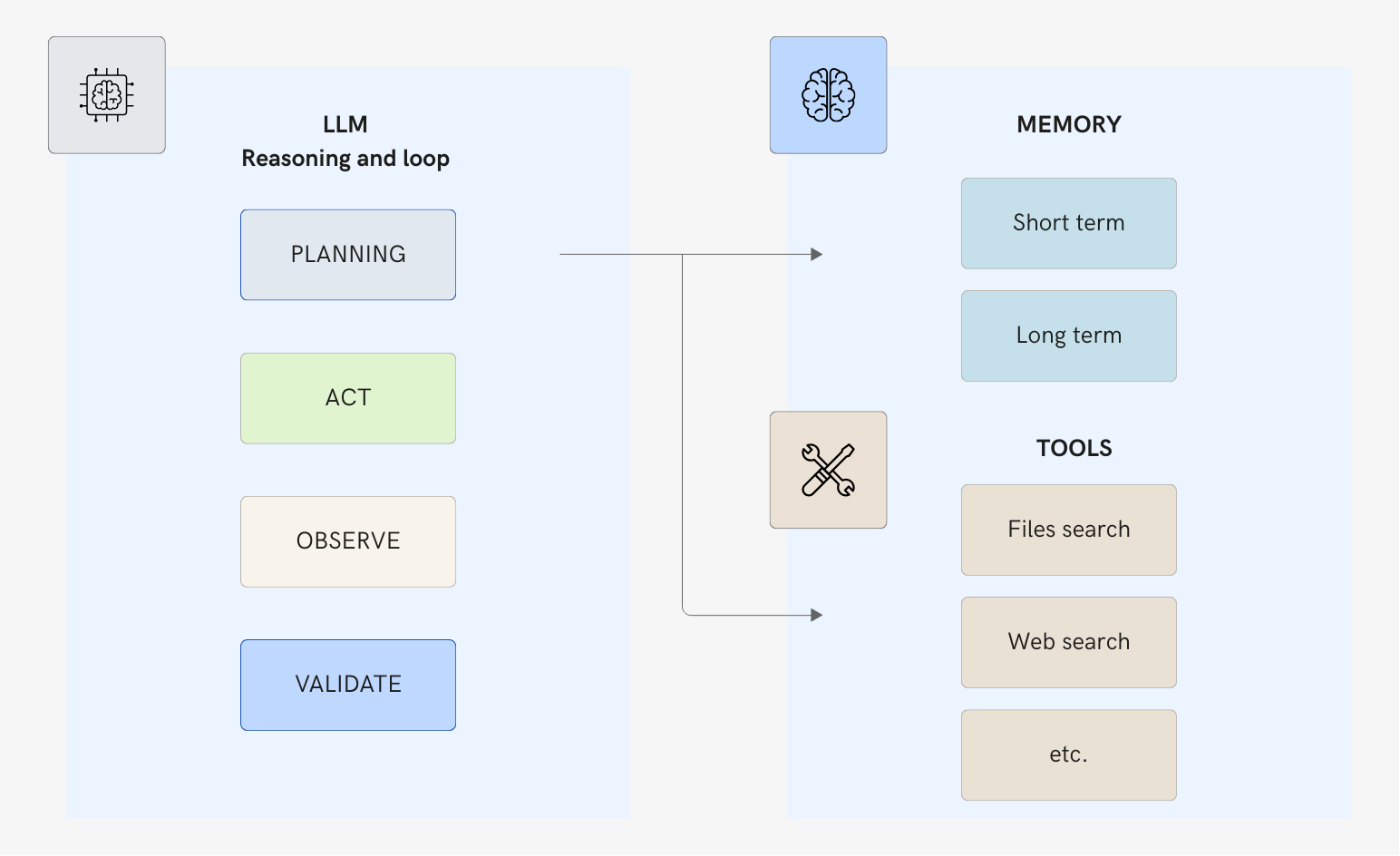

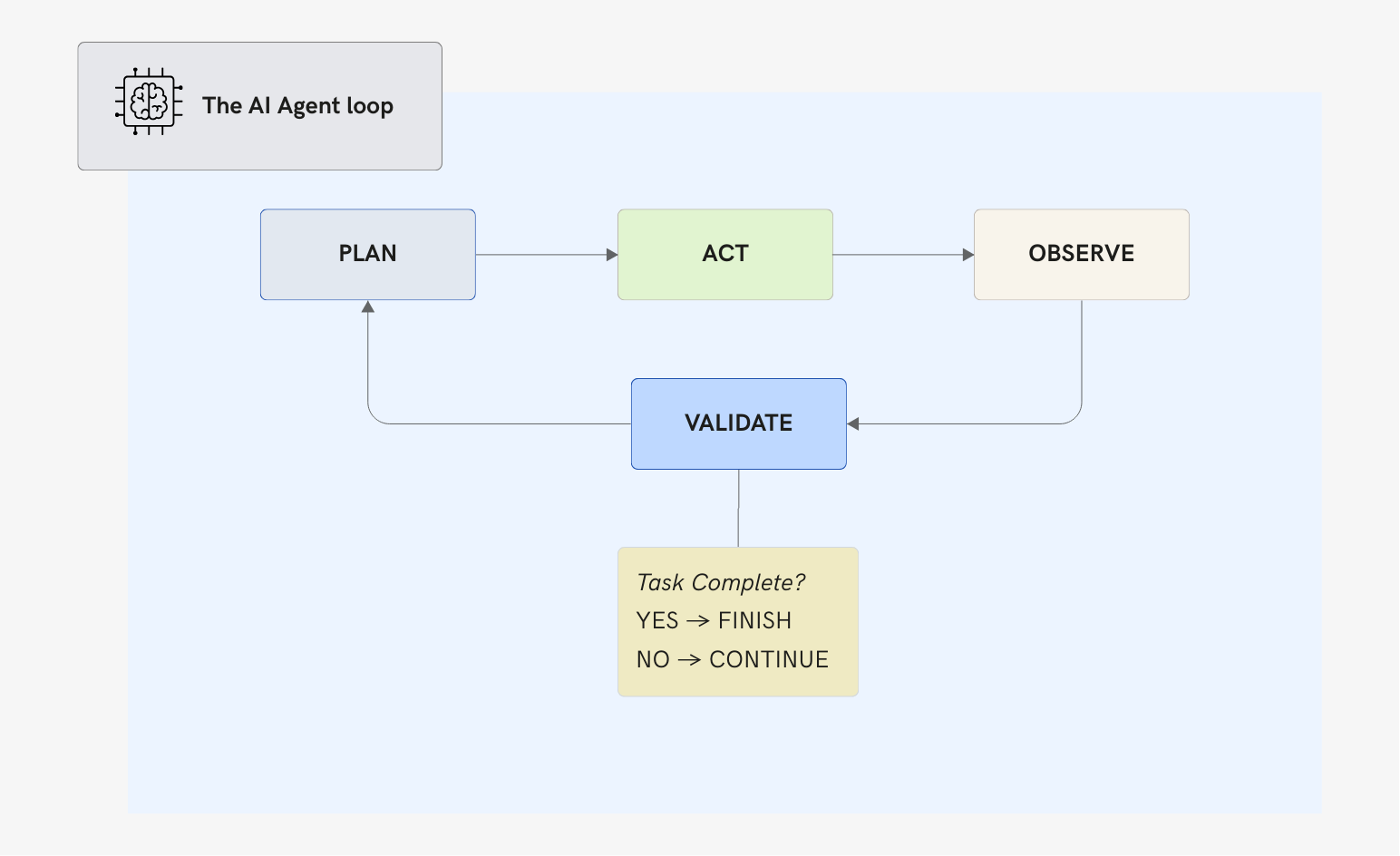

4. The Action-Observation-Reflection Loop

This is the heartbeat of any agent. The thing that makes it "agentic":

Agents plan (decide what to do next), act (execute an action), but they also:

- Observe: Process what happened

- Validate: Did this get us closer to the goal?

- Iterate: Repeat until done (or stuck)

This loop looks elegant on paper. In practice, it's chaos:

- Actions fail in unexpected ways

- Observations get misinterpreted

- Validation is biased or wrong

- The loop gets stuck, repeating the same failed approach forever

Making this loop robust is the hardest part of building production agents.

Workflows vs. Agents: Know the Difference

A critical distinction emerges between reactive AI systems that passively respond to predefined prompts and proactive agentic systems that actively formulate goals and decompose tasks.

The taxonomy proposed in recent research distinguishes agentic AI from traditional AI agents along a spectrum of capabilities. The key differentiation is the degree of autonomy and goal formulation: agentic AI systems not only execute actions, but also decide what to do next based on evolving contexts.

To make it simple, we can distinguish between two main architectures (for more):

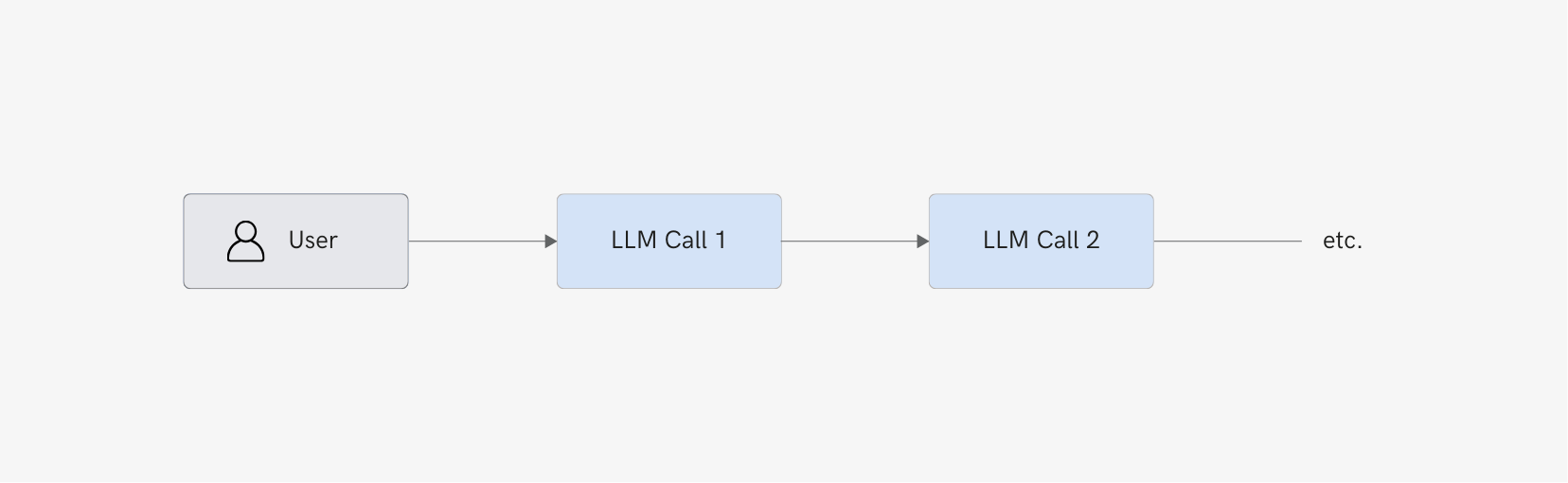

Workflows

Workflows are systems where LLMs execute within predefined paths. You decide the sequence; the LLM adds intelligence to each step.

The flow is deterministic. The LLM makes individual steps smarter, but it doesn't choose what steps to take.

There are many workflow patterns: prompt chaining (breaking tasks into fixed sequential subtasks), routing (classifying inputs and directing them to specialized handlers), parallelization (running multiple LLMs simultaneously on different aspects), orchestrator-workers (a central LLM coordinating specialized sub-tasks), or evaluation loops (using one LLM to check another's output).

Workflows are predictable. Auditable. Consistent. Great for well-defined, repeatable tasks.

Agents: Dynamic Paths

Agents are systems where LLMs dynamically direct their own processes. The LLM maintains control over how it accomplishes tasks.

Autonomy is the defining characteristic of agentic AI, referring to a system’s ability to make independent decisions without step-by-step human guidance. The key difference: agents decide their execution path at runtime.

Give an agent "Research this company and write a competitive analysis." It might:

- Search the web for company info

- Realize it needs financials, query a database

- Find conflicting data, search for more sources

- Synthesize findings

- Realize it's missing competitor info, loop back

- Finally produce the analysis

That sequence wasn't predetermined. The agent figured it out based on what it found.

The selection between workflows and agents is kind of a tradeoff between predictability and power.

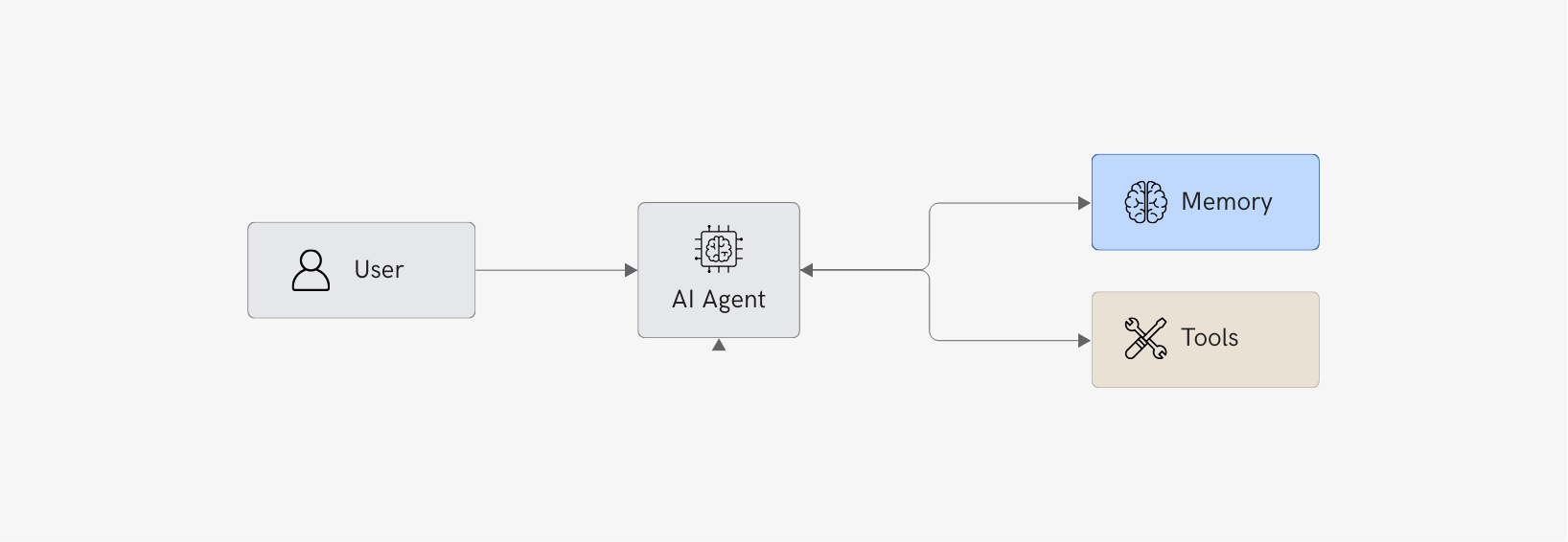

Single-Agent vs. Multi-Agent

In the AI agent architecture, we can also make 2 distinctions:

- single agent that handles everything,

- multi-agent, multiple specialized agents that collaborate.

Single-Agent Systems

One agent, all tasks. Simple. Clean. No coordination overhead.

Works well for:

- Moderate complexity

- Consistent task types

- Simpler reasoning requirements

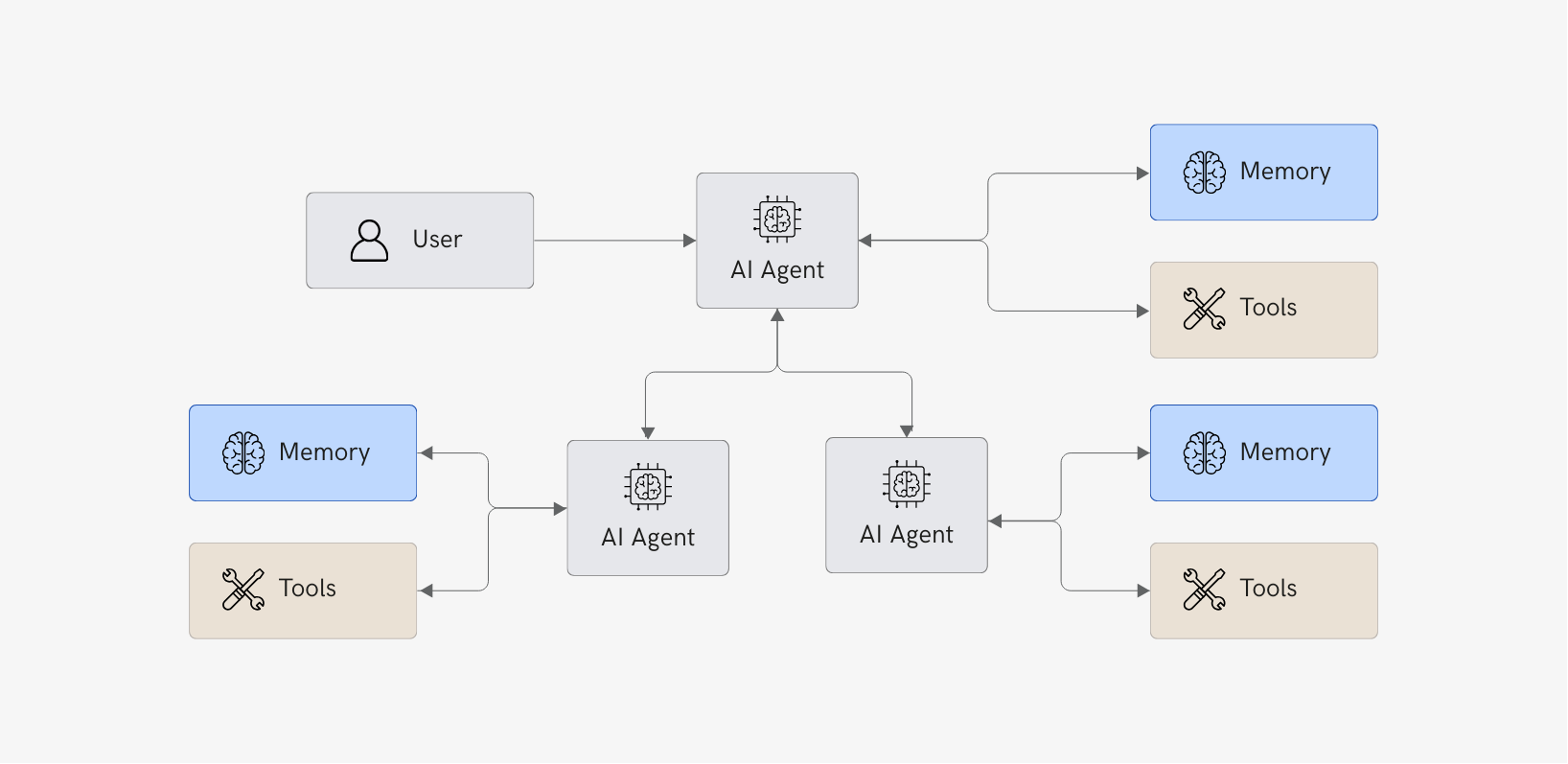

Multi-Agent Systems

Distribute work across multiple AI agents. Think about a multi-agent system like a specialized team. E.g.:

- A "researcher" agent gathering information

- An "analyst" processing data

- A "writer" producing outputs

- An "orchestrator" coordinating

This enables sophisticated workflows but introduces other challenges. AI agents can talk to each other, but they don't always understand each other. This problem might lead to some inefficiency in collaboration for long-horizon problems and complex domains (Flemming et al. 2025) .

This was the easy part: definitions, components, architecture patterns.

2. Real Challenges of Building AI Agents

At every level of their architecture, agents face challenges. The hard part is making agents actually work (e.g., failure taxonomy for deep research agents – Zhang et al 2025).

In the next sections, we'll discuss 3 important challenges (not exhaustive):

- Context engineering (A) — the raw material of reasoning — must be constructed, filtered, and maintained within a constrained space. But how do you feed an agent the right information without drowning it? How do you prevent early errors from contaminating the entire reasoning chain?

- Tools (B) — the interface with the real world — must be selected correctly, invoked with the right parameters, and their results properly interpreted. How do you ensure the agent picks the right tool, formulates valid arguments, and catches silent failures?

- Reasoning (C) — the engine driving the agent loop — must stay coherent across many iterations. How do you prevent goal drift, infinite loops, or the slow accumulation of errors over time?

Each of these is a rabbit hole.

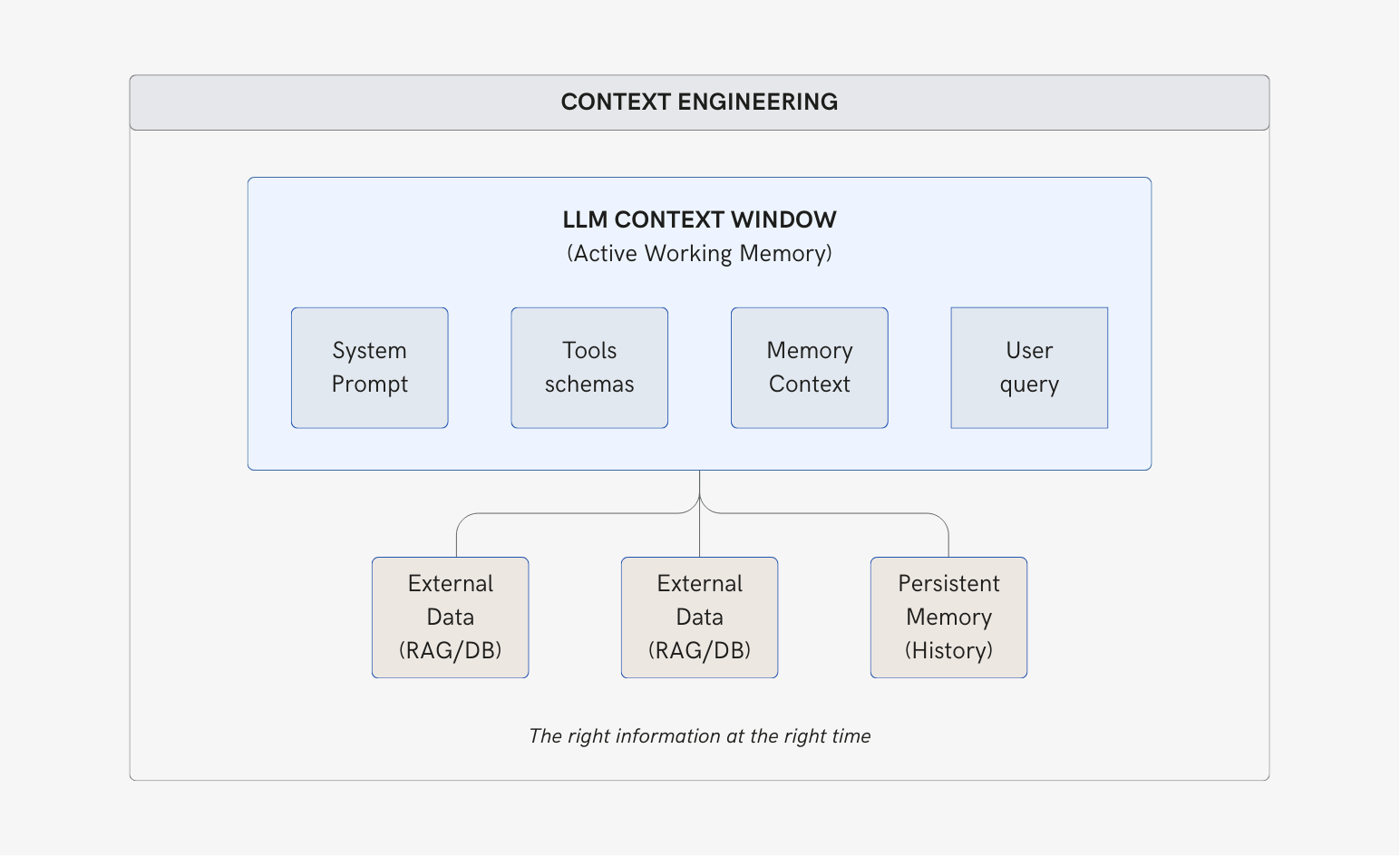

A. Context Engineering:

The Context Window as Working Memory

The context window of an LLM is its active working memory — the finite space (measured in tokens) where the model holds system and user instructions, and the information for the current task, which can include tool schemas and retrieved data. By default, each new inference wipes the slate clean. Old information is gone; new information takes its place.

Context Engineering is the discipline of designing systems that feed an LLM the right information at the right moment. It's not about modifying the model itself—it's about building the bridges that connect it to the outside world: retrieving external data, connecting to real-time tools, and providing memory that grounds its responses.

Why Context Engineering is Hard

Context engineering is anything but trivial. It's an experimental science—one that requires countless iterations, where each experiment reveals a slightly better way (or not) to shape the context.

What happens when an agent receives input? It progresses through a chain of steps and iterations. At each step, the model selects an action from a predefined action space based on the current context (which may include external context). The action executes in the environment and produces an observation. Action and observation are added to the context, forming the input for the next iteration—which may also introduce new context elements. This loop continues until task completion.

The critical pattern: context grows with every step, while output — typically a structured function call — remains relatively short.

Failure Modes of Context

Several failure patterns emerge from context management:

- Context Poisoning: Incorrect or hallucinated information enters the context. Since agents reuse and build upon their context, these errors persist and compound across iterations. One bad piece of data early on can corrupt everything that follows. Here's a simple example we encounter with an agent tasked with fetching data from the web. One website returned a 404 error. Instead of reporting "the page wasn't found," the agent interpreted the 404 as its own failure — and simply stopped. It had confused external feedback with self-evaluation and decided it couldn't continue.

- Context Distraction: The agent drowns in too much past history — old conversations, tool outputs, summaries — and over-relies on repeating past behaviors instead of reasoning fresh. It becomes a pattern-matcher rather than a problem-solver.

- Context Confusion: Irrelevant tools or documents clutter the context, distracting the model and pushing it toward the wrong tool or the wrong instructions. The agent has too many options, and picks poorly.

- Context Clash: Contradictory information within the context misleads the agent, leaving it stuck between conflicting assumptions with no clear resolution path.

The Bigger Window Paradox

Since 2023, context windows have exploded: 128K tokens → 1M tokens → and beyond (Gemini 1.5 Flash supports up to 2 million tokens– roughly 4,000 pages of text). You'd think this solves some issues.

It doesn't.

Here's the twist—bigger windows create their own problems. Models tend to degrade with large contexts. The infamous "lost in the middle" effect means agents become confused, hallucinate more, or simply stop performing at their usual level. More context doesn't mean better reasoning (e.g., study on context rot). In addition, even with caching, long inputs are expensive. Token consumption scales with context size (or infrastructure needs can spiral quickly). Also, some real agentic scenarios often need even more context than these windows provide.

Many systems implement truncation or compression strategies. But it also has its own challenges: aggressive compression inevitably loses information. The problem is fundamental: an agent must predict its next action based on the entire prior state — and it's difficult to reliably predict which observation will become critical ten steps later.

Context Retrieval

Specific challenges emerge when retrieving the right context for a given task:

- Too many tokens (retrieved context > needed context): Some tools — web search, file retrieval — can return massive amounts of tokens. A few searches can quickly accumulate tens of thousands of tokens in conversation history. Without filtering mechanisms (reranking, summarization), the context becomes unmanageable.

- Need for massive context (needed context > supported context window): Sometimes the agent genuinely needs a large amount of information to answer a question. This information typically can't be retrieved in a single search query, leading to "agentic search" — letting the agent call search tools repeatedly. The problem: context grows rapidly until it no longer fits in the available window.

- Niche information (retrieved context ≠ needed context): Agents may need to reference niche information buried across hundreds or thousands of files. How does the agent reliably find this information? If retrieval fails, the recovered context won't match what's actually needed to answer the question. Semantic search alone isn't always enough—alternatives or complements become necessary.

Such challenges are directly related to the retrieval architecture of the agent (full context or RAG): the agent needs to access proper retrieval tools to be able to gather the relevant context for the specific task:

- long-context when the agent needs a global understanding (complex contracts, market studies, etc.) and the answer depends on patterns across many places, i.e., the cases where you need an exhaustive assessment of the sources.

- Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) when the agent needs to search for a specific information of facts.

- In some cases, you need both: first retrieve specific information to filter your company's knowledge and then expand the analysis on the filtered documents.

Agent Memory: Where Context Engineering Becomes an Art

With Memory, the goal isn't to get more data into the context—it's to build systems that make the best possible use of the available context window, keeping essential information accessible when it matters.

Agent memory exists to retain the information needed to navigate between tasks, remember what worked (and what didn't), and anticipate next steps. Building robust agents means thinking in layers, combining different types of memory with different purposes.

In practice, modern systems adopt a hybrid approach:

- Short-term memory for speed — the immediate context, recent actions, current plan

- Long-term memory for depth — persistent knowledge, user preferences, past interactions

Some architectures introduce additional layers:

- Working memory: Information held until task completion, without cluttering long-term storage

- Procedural memory: Behavioral learning from experience — patterns of what works

- Negative memory: What didn't work — failed tools, irrelevant documents, unsuccessful approaches — to avoid repeating the same mistakes within a session

- etc.

The Hard Questions of Memory Design

Designing an effective memory system for agents raises several fundamental questions:

- What to keep in the agent's memory? Not all information has equal value. Store too little, and the agent loses critical context. Keep too much, and you create noise that confuses the model.

- When to retrieve? Deciding the optimal moment to query long-term memory requires balancing completeness against efficiency. Too many queries slow the agent down. Too few deprive it of relevant information.

- How to handle obsolescence? Information ages. What was relevant 50 interactions ago may have become outdated—or even counterproductive to recall.

These challenges make memory management one of the most complex aspects of context engineering, requiring constant trade-offs between completeness, performance, and cost.

Other Context Engineering Challenges

Beyond memory and retrieval, context engineering faces a long list of additional problems that are related to building AI agent infrastructure:

- Query understanding: Transforming user requests into a form the system can actually use. Users formulate requests ambiguously, incompletely, or in formats poorly suited to vector search. Techniques like query rewriting, query expansion (generating multiple queries), and query decomposition (breaking into sub-questions) attempt to address this—with variable success.

- Ranking and relevance: Determining which documents are truly relevant among returned results. Vector similarity doesn't guarantee functional relevance—a document can be semantically close without containing the information actually needed.

- Heterogeneous formats: Agents interact with data in varied formats — text, tables, images, PDFs, web pages, etc. Each format requires specific processing for extraction and normalization.

- Multi-modality: Integrating information from different source types (text + images + structured data) into a unified context remains an open problem.

- Citations and traceability: Enabling the LLM to cite sources accurately requires maintaining metadata throughout the entire processing chain—from storage to context injection.

- Inter-document conflicts: When multiple documents contain contradictory information, the system must either resolve the conflict, flag it, or prioritize certain sources — all complex decisions to automate.

- Latency and user experience: Every retrieval step, reranking pass, or intermediate processing adds latency. The balance between result quality and acceptable response time heavily constrains architectural choices.

- etc.

These challenges illustrate the systemic complexity of context engineering — and why robust architectural approaches matter.

B. Function Calling: When Tools Become a Liability

With tools, agents acquire capabilities (searching the web, sending e-mail, retrieving data, etc.) – increasingly common with the rise of Model Context Protocol (MCP). To execute such function, agents need to call the relevant tool(s) when they need it. There are different function calling modes:

- Auto mode: The model can choose whether to call a function or not. No constraints imposed. This is the most flexible mode—but also the most unpredictable. The model may decide to respond with text when a tool call was actually needed.

- Required mode: The model must call a function, but the choice remains free among all available functions.

- Constrained mode: The model must call a function from a specific subset, with direct constraints on token logits.

Each mode trades off flexibility against predictability.

In all cases, as agents acquire more capabilities — their action space becomes more complex. The consequence is counterintuitive: the more tools an agent has, the more likely it is to pick the wrong one or take an inefficient path. The heavily-armed agent paradoxically becomes less effective.

Why Tool Use is Harder Than It Looks

One of the core challenges of function calling lies in the quality of prompting required for the LLM to use tools correctly. The decision to use a tool depends on its textual description — that's the only guide the model has to understand when and how to use it.

LLMs frequently make incorrect tool selections or use them in a wrong way (e.g., calling a tool that requires a preliminary step). To prevent these errors, tool descriptions must precisely define:

- When to use the tool: Specify the scenarios or conditions that trigger a particular tool's use. Without this clarification, the model may invoke a tool in an inappropriate context — or ignore a relevant tool entirely.

- How to use the tool: Provide expected inputs, required parameters, and desired outputs. The model must understand exactly what arguments to pass and what it will receive in return.

- When NOT to use the tool: Explicitly defining exclusion cases is just as important. Without these guardrails, the model may overuse certain tools or apply them to situations they weren't designed for.

These clarifications might seem simple. They're not. They lead to countless errors in practice.

The Argument Formulation Problem

Even when the correct tool is selected, formulating arguments poses considerable challenges:

- Parameter extraction: The model must extract appropriate values from context and format them correctly.

- Types and formats: Typing errors (string vs. integer, date formats, JSON structure) are frequent and generate silent failures or unexpected behaviors.

- Optional vs. required parameters: The model may omit required parameters or provide values for parameters that don't exist.

Tool Hallucination

Models tend to hallucinate calls to non-existent functions or use incorrect signatures. In multi-agent systems where each agent has a dynamic tool set, this phenomenon triggers error cascades that are difficult to diagnose.

The agent can "invent" a tool it believes should exist, generating particularly insidious silent failures.

This manifests in several ways:

- Inventing plausible but non-existent function names

- Using parameters that don't exist in the actual schema

- Confusing tools with similar names or functionalities

Workflow Short-Circuiting

A particularly problematic behavior: LLMs tend to "skip" steps in planned action sequences. Faced with a task requiring multiple tool calls, the model may decide to provide a direct text response without executing the planned actions — creating inconsistencies between the state perceived by the agent and the actual system state.

The agent thinks it did something. It didn't. And everything downstream is now wrong.

To be reliable, function calling requires a complete architecture: schemas precise enough to eliminate ambiguity, execution logic that governs timing and sequencing, message handling that keeps conversational flow coherent, integration layers that survive failures and format changes, validation that catches malformed inputs before execution, state management that remembers what was already tried, etc.

Each layer is a potential failure point. And they compound: a bad schema leads to the wrong tool, the wrong tool returns an unexpected format, the unexpected format breaks message handling, broken flow corrupts state. One weak link, and the whole chain collapses.

Building agents that use tools reliably means building all of this — not just writing a function and hoping the LLM figures it out.

C. The Reasoning Loop: The Heart of the Problem

The Challenge of Autonomous Reasoning

Reasoning is the core of agentic intelligence — it's what separates an agent from a simple chain of predefined inferences. But making a fundamentally probabilistic system "reason" is a major challenge.

An LLM, by design, predicts the most likely next token given the context. It has no "reflection" in the human sense—no native ability to pause, evaluate, reconsider. Every generation is a statistical prediction, not a deliberation.

Asking such a system to "reason" through complex tasks means hoping that emergent behavior from text prediction produces logical coherence. Sometimes it works. There's no guarantee it will.

Here's the key difference: a human knows when they don't know. They can recognize a dead end, identify a reasoning error, and decide to change their approach. LLMs lack this intrinsic capacity. They can generate text that looks like reflection — but without genuinely evaluating the quality of their own reasoning.

The Action-Observation-Reflection Loop

Agentic architectures attempt to compensate for these limitations by structuring LLM behavior into an iterative loop:

- Action: The agent decides and executes an action (tool call, content generation)

- Observation: The agent receives the result of its action

- Reflection: The agent evaluates whether the result meets the objective

- Iteration: The agent decides to continue, adjust, or terminate

Through this loop, agents are able to evaluate and adjust their actions based on self-awareness and past experiences (at least in theory). This metacognition, or "thinking about thinking," is an important concept in the development of agentic AI systems, but it raises fundamental problems.

The Iteration Problem

When to iterate? By definition, a probabilistic system has no objective criteria for deciding whether an additional iteration is necessary. The LLM can:

- Declare a task complete when it's actually incomplete (false positive)

- Continue iterating indefinitely without real progress (infinite loop)

- Stop arbitrarily when facing a difficulty it could actually overcome

What criteria for evaluation? Even when asking the LLM to evaluate its own work, on what basis can it judge? It only has access to textual context — not to external "ground truth." Its evaluation remains a probabilistic prediction, subject to the same biases as its initial generation.

Consider a concrete example: an agent searching for insights into a database for specific information (Agentic RAG). The agent queries the database. It gets some results. Now what?

- How does it know if the search succeeded? The database returned documents—but are they the right documents? Are they complete? Did the query miss relevant information buried under different keywords?

- How does it know when to stop? If the first search returns nothing, should it reformulate the query? Try synonyms? Search a different index? How many attempts before concluding the information genuinely doesn't exist versus the search strategy was wrong?

- How does it evaluate completeness? The user asked about "all contracts with termination clauses." The agent found 12. But there are 200 contracts in the database. Did it find all relevant ones, or did 15 slip through because they used "cancellation provisions" instead?

Unlike a human analyst who might remember "there was something about this in last quarter's report," the agent has no prior knowledge of what exists in the database before searching. It can't recognize gaps in its results because it has no baseline to compare against. It can only evaluate what it retrieved — not what it missed. The agent declaring "I found everything" is just another prediction, subject to the same limitations as every other LLM output.

Degradation on Long Reasoning Chains

Complex tasks require dozens of iterations. On these long chains, several degradation phenomena appear:

- Goal drift: Over iterations, the agent progressively loses sight of the initial objective. Tactical decisions become inconsistent with the global strategy. After 15-20 steps, the agent may pursue sub-objectives that no longer contribute to the main task.

- Error accumulation: Each sub-optimal decision compounds with the following ones. A misinterpretation at step 3 can invalidate all work from steps 4 to 10—without the agent realizing it.

- Context fatigue: Even with large context windows, reasoning quality degrades as context grows heavier. The agent "forgets" critical elements mentioned at the beginning, or gives too much weight to recent events (recency bias).

- Perseveration: The agent can stubbornly persist with an ineffective approach, repeating variations of the same failed strategy rather than fundamentally reconsidering its method.

The Absence of Behavioral Guarantees

Integrating LLMs into operational workflows faces a fundamental challenge: the absence of formal behavioral guarantees.

Unlike traditional systems where state transitions are deterministic and statically verifiable, LLMs produce probabilistic action sequences whose conformity to the prescribed workflow cannot be ensured a priori.

The fundamental problem: no textual instruction can guarantee behavior. You can prompt an agent with precise rules ("always verify before concluding," "never skip steps"), but the LLM remains free to ignore them if probabilistic pressure pushes it toward a different generation.

Models show a systematic tendency to bypass intermediate verification steps when they believe they have a direct answer. On tasks requiring an explicit sequence (planning → execution → observation → validation), the model frequently attempts to provide an immediate text response without executing the prescribed data acquisition primitives.

On tasks requiring multiple sequential actions, models exhibit instability in respecting the sequence. After a first successful action, they may either consider the task prematurely complete (incorrect validation) or repeat the same action indefinitely without progressing (infinite loop).

This reality has profound implications:

- Critical workflows cannot rely on the model's "good will"

- Guardrails must be architectural, not just textual

- Validation must be external to the generating system, not self-referential

A major technical difficulty: the impossibility of rollback in transformer architectures. Once an LLM has generated a sequence corresponding to an action (state mutation, text response), that action is irreversible. There's no "undo" at the model level.

What's Actually Needed

Facing these limitations, intelligent control systems become necessary. Not more prompts. Not better instructions. Architecture.

Here's what separates agents that work from agents that feel ‘dumb’:

1. Memory that survives the workflow

Not summaries. Not just the context window. Actual structured memory: what happened, what the agent decided, what failed, what it should avoid next time. If the agent forgets its own steps, it repeats mistakes endlessly. Memory must be explicit, persistent, and queryable — not implicit and ephemeral.

2. Tools the agent can actually use

Most people expect the model to "figure out" which tool to call. It can't — at least not reliably. Tools need crystal-clear signatures, explicit return formats, and unambiguous documentation: what each tool does, when to use it, what a good output looks like. Once tools are explicit, reasoning stops derailing.

3. Goals that force structure

A good agent goal is specific, measurable, and decision-driving: Vague goals produce vague behavior. Structured goals produce structured execution.

4. Recovery paths for when things break

The easiest way to spot a weak agent: one bad tool call and the entire flow collapses. Production agents need retry logic, fallback plans, diagnostic capabilities, and the ability to continue working even when one component fails.

5. Transition validation

Verify that each step is legitimate before allowing the next — based on objective criteria, not the LLM's self-evaluation. The agent saying "I'm done" doesn't mean it's done. External validation must confirm it.

6. Drift detection

Identify when the agent strays from the initial objective, loops without progress, or is about to declare premature victory. Without this, agents slowly wander off course — and you won't notice until the output is garbage.

7. Strategic coherence

Preserve an "objective memory" that isn't subject to the LLM's contextual drift. The agent at step 30 must remember what the agent at step 1 was trying to accomplish—even if the context window has long since moved on.

etc.

Note that it's always possible to train a model to make better tool choices and improved its reasoning over proprietary loops. However, this approach comes with its own challenges (in particular when you are integrating multiple LLMs).

To ship production-ready agent, agents don't need more "thinking." They need structure. And no open-source project provides such structure.

Controls cannot be prompts. Prompts are suggestions. Agents ignore suggestions when probabilistic pressure pushes them elsewhere. The controls must be architectural — imposing constraints at the orchestration level, not the generation level. The difference between demo agents and production agents often comes down to whether these controls exist.

3. At Lampi AI

At Lampi, we build confidential AI agents for finance professionals: private equity analysts, investment bankers, M&A advisors, legal teams. The kind of users who can't afford "mostly works." When you're screening 100 companies for a deal, reviewing 200 legal agreements, or generating an 80-page investment memo, "the agent got confused" isn't an acceptable outcome.

This forced us to confront every challenge described above — context engineering, function calling, reasoning loops — not as theoretical problems, but as blockers for shipping to production.

We've been building AI agents since 2023 — long before "agentic AI" became a buzzword. After hundreds of iterations, we finally came up with a multi-agent architecture where specialized agents work together — each with a clear role, strict boundaries, and no ability to cut corners.

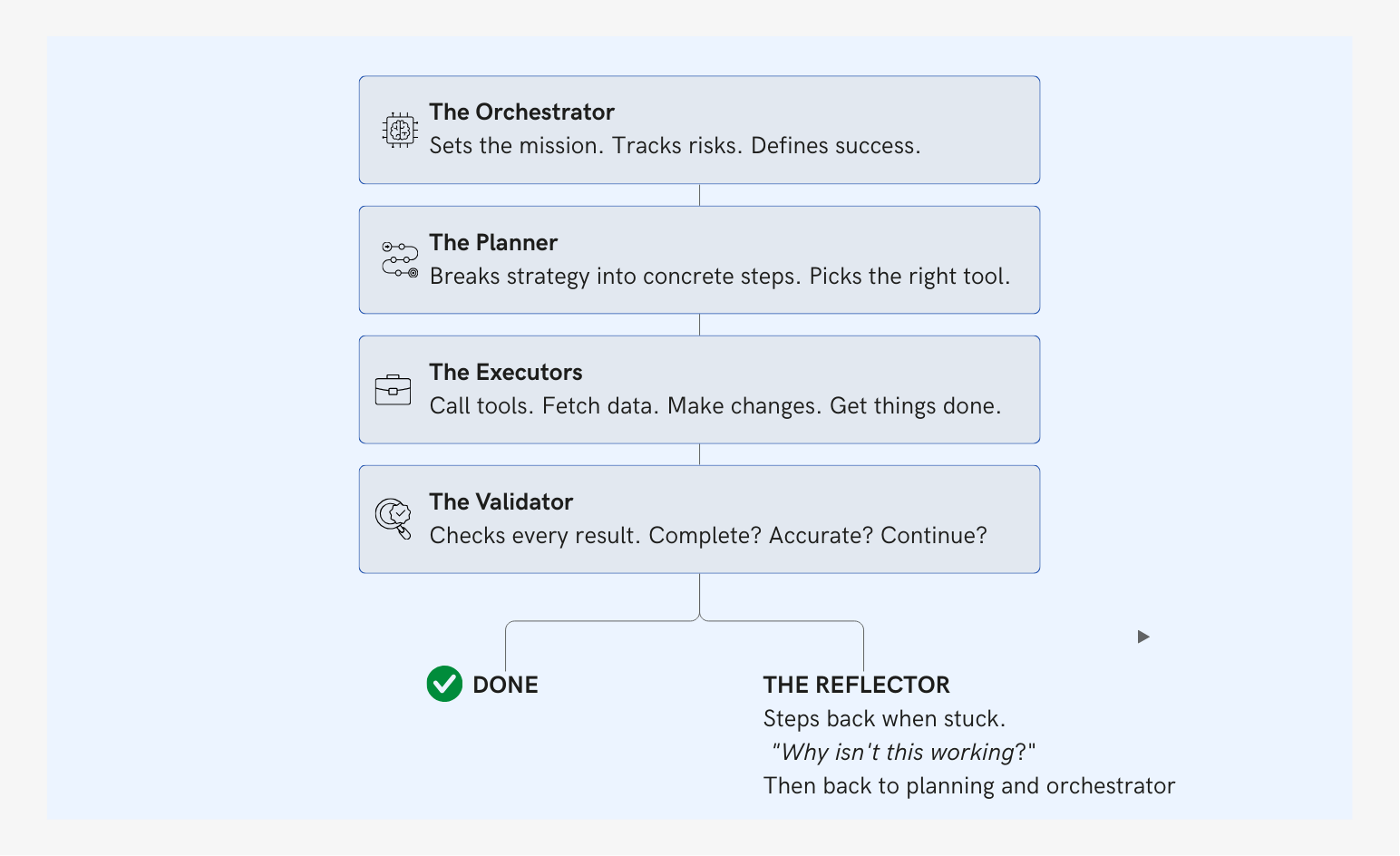

Most AI agent frameworks run a single reasoning loop: plan, act, observe, repeat. Lampi separates these roles into distinct specialized agents:

Let's say a user asks: "Prepare a competitive analysis of three potential acquisition targets in the European fintech space."

Here's how the agents collaborate:

- The Orchestrator receives the request and frames the mission: identifying targets, analyzing each across financial, strategic, and risk dimensions, comparing them, and producing a structured output. It defines success criteria: each target must have verified financials, market positioning, and potential synergies documented.

- The Planner breaks this into concrete steps: (1) search for European fintech companies meeting size and sector criteria, (2) gather financial data on each candidate, (3) research market positioning and competitive landscape, (4) identify risks and red flags, (5) synthesize into comparative analysis.

- The Executors get to work. One searches the web for companies. Another queries internal databases for any prior work on these targets. Another pulls financial data from connected sources. Each executor operates independently, focused on its assigned task.

- The Validator checks every result. Did the search return companies that actually match the criteria? Are the financials complete, or missing key metrics? Is the market analysis substantive, or shallow? If something fails validation—say, one target has no reliable financial data — the Validator flags it and routes back to the Planner.

- The Planner adapts. Maybe it substitutes a different target. Maybe it tries alternative data sources. The plan evolves based on what's actually possible.

- The Reflector kicks in if the cycle stalls. Three attempts to find financials for Target B, all failed. The Reflector asks: "Is this target even viable? Should we replace it entirely, or flag it as high-risk due to opacity?" .

Throughout, the Orchestrator maintains strategic coherence. Even if the Planner pivots tactics, the Orchestrator ensures the final output still answers the original question: a comparative analysis of three viable acquisition targets, not a random collection of partial research.

This isn't a single LLM trying to hold everything in its head. It's a team — with separation of concerns, clear handoffs, and checks at every stage.

Here are just some examples of innovation that was required to make a reliable architecture:

- Architectural Behavior Enforcement: As explained, prompts can't guarantee behavior. We solved this by building a constrained state machine that governs agent behavior at the architectural level — not the prompt level. The agent physically cannot skip steps because the invalid transitions don't exist in its action space. The orchestrator intercepts every action and enforces the workflow structure to ensure the executors perform their tasks.

- Multi-Level Planning with Strategic Coherence: Single-level planning breaks down on complex tasks. After 15-20 actions, agents forget their original objective and start optimizing locally for whatever's in front of them. We implemented a two-tier planning architecture: a persistent strategic meta-plan that holds the big picture (objectives, hypotheses, constraints, success criteria, etc.), and ephemeral tactical plans that handle immediate execution. When tactical plans fail repeatedly, the system forces a strategic revision. When tactical plans succeed, their key decisions get archived — creating an episodic memory the agent can consult to avoid repeating past mistakes. This separation means the agent maintains strategic coherence even across sequential actions, because the meta-plan acts as a constant anchor that gets re-injected into context at every iteration.

- Post-Mutation Revalidation: A tool returning "success" doesn't mean the action worked. A database write might confirm syntactically while failing semantically. We built a revalidation layer that intercepts mutations and forces verification before the agent can proceed.

- Dynamic Tool Provisioning: More tools don't make agents smarter — they make agents more confused. We implemented phase-aware tool filtering: at each stage of execution, the agent sees only the tools relevant to its current task. This reduces the action space dramatically, eliminating entire categories of errors while improving response quality.

- Multi-Level Memory Architecture: Context windows are finite. Agents forget. Past mistakes get repeated. Irrelevant information pollutes reasoning. We built a hierarchical memory system with distinct layers, including:

- Working memory: Structured state including transition logs, active plans, and cognitive health indicators

- Episodic memory: Archived tactical plans that preserve what was tried and why it failed

- Negative memory: Documents and approaches explicitly marked as unhelpful, filtered from future retrievals or strategies

- Strategic anchoring: The orchestrator always ensures that the initial goal is respected.

- etc.

These innovations are just the tip of the iceberg. Building agents for production requires work across entire disciplines: data processing and normalization across heterogeneous formats, security, governance frameworks, full traceability with citation chains, latency optimization, reliability engineering, evaluation, model flexibility, real-time observability, etc.

Ask an AI agent to produce a professional M&A pitch deck — the kind that requires analyzing a target company, researching the market landscape, defining a transaction process, identifying comparable deals, gathering data on each comparable, checking for relevant previous work, designing a slide structure, and actually building the deck – all the tasks an analyst would do in 2 weeks. Today, no agent in the world can do that in a single loop — or at least not professional enough to actually be used (with complete and exhaustive fact-based insights, citations, structure, etc.).

The problem isn't the LLM's intelligence. It's the architecture. Complex tasks have structure. They have dependencies. They have moments requiring deterministic precision and moments requiring creative reasoning.

That's why we built AI Grid Agents.

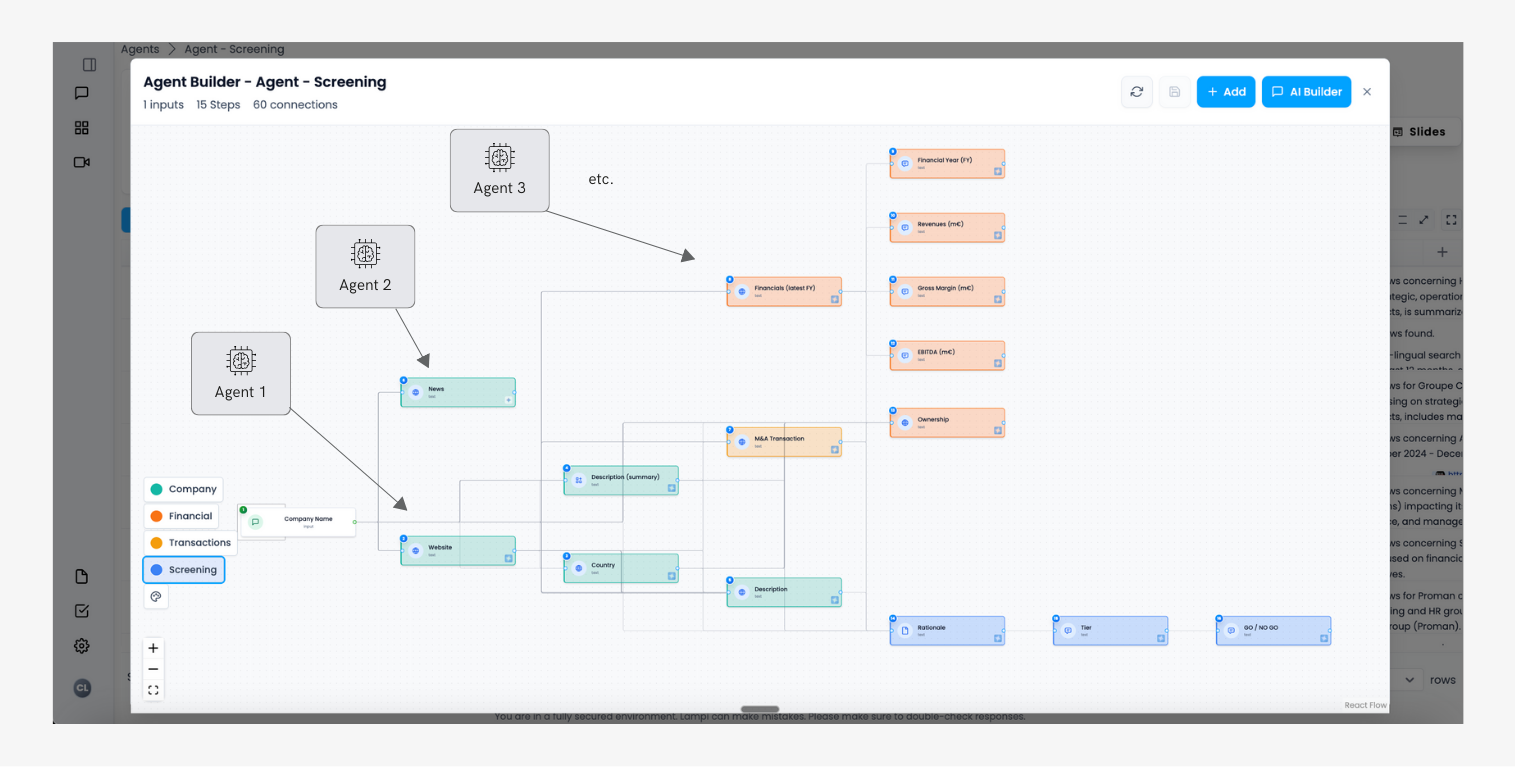

The Grid Agent Architecture

The AI Grid Agent is a complex multi-agent orchestration system that sits between workflows and AI agents.

The core insight: decompose complex tasks into a grid where each step is handled by a specialized agent with bounded autonomy.

Think of it like an intelligent spreadsheet where each column represents a step in the workflow. Each column is a step in the workflow: "Analyze company," "Research market," "Find comparables," "Gather financials," "Build slide."

The workflow structure is deterministic – but within each step, the agent has autonomy — choosing which tools to use, how to interpret the data, what to include in its output, iterating, etc.

The output of each agent is delivered into the grid, which allows:

- to bring a complete transparency for each step,

- to run the workflow on a multiple different topics at once (reviewing independently multiple agreements, assessing a list of companies, etc.).

This hybrid approach gives us the best of both worlds:

- Predictability — you know what happens, in what order

- Flexibility — agents adapt to messy real-world data

- Scalability — process 100 entities the same way you process

- Auditability — trace any output back to its source, step by step

This architecture can power hundreds of workflows. It allows us to replicate the most complex processes that analysts perform daily — the kind that follow a clear structure, but require constant adaptation to messy reality.

Most professional workflows share a pattern: a defined sequence of steps, but with endless variation in execution. Screening targets follows the same methodology, but every company is different. Building a pitch deck follows the same template, but every deal tells a unique story. Today, all production architectures favor predefined static workflows over open-ended autonomy. In fact, 80% of production cases use structured control flow.

In the Grid, Agents operate within well-scoped action spaces rather than freely exploring environment. It gives you both: the determinism of workflows to ensure consistency and auditability, and the flexibility of agents to handle the unpredictable. Structure where you need it. Intelligence where it matters.

Conclusion

Building production-ready AI agents isn't about having the smartest model or the most tools. It's about engineering systems that work when no one's watching — at 2am on a Sunday, processing the 87th document, on the edge case no one anticipated.

The challenges are real: context that poisons itself, tools that get misused, reasoning loops that drift or never terminate. Most agent projects fail not because the LLM isn't capable, but because the architecture around it doesn't enforce the discipline that reliable systems require.

At Lampi, we've learned that the difference between a demo and a production system comes down to one thing: architectural guarantees, not hopeful prompts.

Multi-agent orchestration. Enforced workflows. Mandatory verification. Intelligent memory. Grid-based decomposition for complex tasks. These aren't features — they're the foundation that makes everything else possible.

Ready to see what production-ready AI agents actually look like?